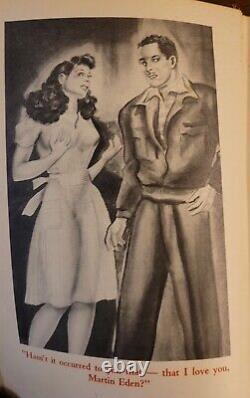

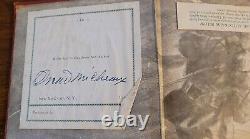

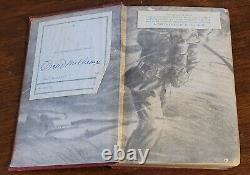

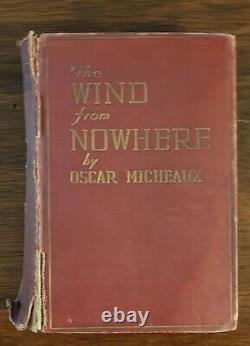

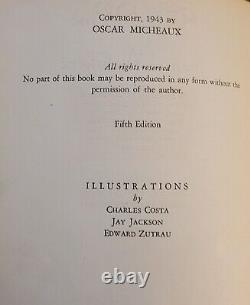

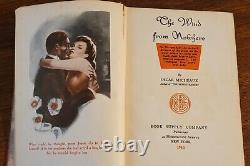

OSCAR MICHEAUX AFRICAN AMERICAN MOVIE DIRECTOR SIGNED 5th Edition BOOK

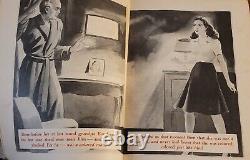

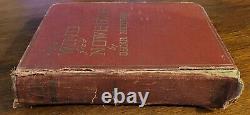

The Wind From Nowhere by Oscar Micheaux. Poor; spine torn; presentation copy signed by author. 5th edition worn, shaken edge wear, reading copy. Oscar Devereaux Micheaux was an African-American author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Oscar Micheaux, in full Oscar Devereaux Micheaux, born January 2, 1884, Metropolis, Ill. Died March 25, 1951, Charlotte, N. , prolific African American producer and director who made films independently of the Hollywood film industry from the silent era until 1948. Also Known As: Oscar Devereaux Micheaux. Born: January 2, 1884 Metropolis Illinois. Died: March 25, 1951 Charlotte North Carolina.

In 1917 he was approached by an African American film company for movie rights to The Homesteader. He refused the offer but liked the idea and made his own film version, thus launching his career as an independent filmmaker. Between 1919 and 1948 he wrote, produced, directed, and distributed more than 45 films for African American audiences, who watched these "race" (all-black) films in the 700 theatres that were part of the ghetto circuit. Micheaux was one of the few black independents to survive the sound era, and he did so largely because of his tenacity, personal charisma, and talent for promoting his work. While on promotional tours, he used his completed films, which he often distributed by hand to waiting theatres, to secure from personal investors the financing for his next project.

Micheaux's features emulated familiar Hollywood genres, and he used a modest version of the studio star system to lure audiences to his movies. His gangster films, mysteries, and jungle adventures featured Lorenzo Tucker (called the "coloured Valentino"), Ethel Moses (the "black Harlow"), and Bee Freeman (the "sepia Mae West"), among others. Despite Micheaux's understanding of certain Hollywood conventions, his films reveal a consciousness of race as a force in the lives of African Americans, and some deal directly with racial issues; these include his examination of white prejudice (Within Our Gates, 1920), interracial romance (The Exile, 1931), and skin-tone issues within the African American community (God's Step Children, 1937). Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Micheaux's necessarily low budgets forced him to cut costs and resulted in technically inferior films with poor lighting, little editing, flubbed lines, continuity problems, and poor sound. Yet he treated issues that were important to his audience, offered an alternative to the stereotyping of blacks by Hollywood, and successfully operated outside the mainstream film industry during the powerful studio era. Black filmmakers have struggled for representation as long as the movies have existed. As Hollywood took shape in the early half of the 20th century, Black directors were already looking for ways to push back on prevailing stereotypes.

From the "uplift" films of the 1910s, produced via initiatives at the Tuskegee and Hampton Institutes, to the naturalistic shorts made by William Foster in Chicago, and the work of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company - the first Black-owned film production enterprise in the United States - there was no shortage of examples. The most prolific and tireless voice during this period was Oscar Micheaux, who blazed trails in Black American cinema beginning with his 1919 feature debut, "The Homesteader, " the first feature film written and directed by an African American. It's been 90 years since he became the first Black filmmaker to produce a sound feature film with "The Exile;" it's been 70 years since his death. And still, Micheaux's impact hasn't been fully measured and recognized by Hollywood.As the HFPA faces a major reckoning over its diversity issues, and the awards infrastructure faces major questions about representation, Micheaux's underappreciated legacy is worth another visit. Oscar Micheaux Finally Premieres at Cannes, 70 Years After His Death. How'The Story of a Three-Day Pass' Became the First Film to Show Black Power on Screen. Micheaux produced and directed films at a time when Black people were still considered (by a virulently racist white establishment) undeserving of their humanity, let alone the freedom to tell their own stories. His "nothing is impossible" self-sufficiency, and the DIY nature of his films (arguably anointing him the first independent filmmaker) paved the way for indies that would follow.

The child of a former slave, and America's preeminent Black filmmaker for almost three decades, Micheaux started the Micheaux Film Corporation and made about 44 films, often as writer, director, and producer. Like Hitchcock, he often cameoed in his own work. This was the early 1920s. Considering the racial tenor of the times, it's certainly apropos to wonder how a Black man of very humble roots, with a limited education, and virtually no technical or artistic training, became a filmmaker of note and created a film production company with a reputation that endured - until it didn't. BODY AND SOUL, Paul Robeson, 1925. "Body and Soul, " Paul Robeson, directed by Oscar Micheaux, 1925.His legacy has not been entirely disregarded; contemporary Black filmmakers like Spike Lee have been vocal about Micheaux's influence. Lee even once called Micheaux his "idol" who inspired me to do my first film. In 1986, the Directors Guild of America honored Micheaux with a lifetime achievement award. In 2010, the US Postal Service issued a Micheaux commemorative stamp. In 2019, Micheaux's masterpiece, "Body and Soul, " was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry for being culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.

" The 1925 "race film featured Paul Robeson, then 27 years old, in his motion picture debut. In 2017, HBO announced that it would develop a Micheaux biopic; Tyler Perry, whose own ascent mimics that of Micheaux's, was on board to star.

Yet Micheaux has yet to be recognized in any way by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, aka the most famous and prestigious organization in the film world. Note that the statuette it hands out each year to countless artists and crafts people is named Oscar. That suggests either total ignorance, or perhaps a lack of appreciation among Academy brass for what he was able to accomplish as a Black man in Jim Crow America, but it's time to do something about it. One idea, whether the Academy or another organization goes for it, would be an annual award named after Micheaux designed to celebrate pioneering work of other relatively unknown Black artists of yesteryear.

There's gold in them thar hills. After all, it's not just Micheaux whose career has been rendered inconsequential. They diverged from the aesthetics of earlier Black films, like the inexpensive melodramas made by Micheaux, and imbecilic depictions of Black people in Hollywood fare.

The intent was to appeal to the mainstream on their own terms. Many of those films are presumed lost. DARK MANHATTAN, Cleo Herndon, Ralph Cooper, Jess Lee Brooks, 1937. "Dark Manhattan, " Cleo Herndon, Ralph Cooper, Jess Lee Brooks, 1937.

Everett Collection / Everett Collection. The average movie buff will likely know about the films of Black performers and filmmakers who thrived, to an extent, prior to the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 - Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Dorothy Dandridge, and the first Black Oscar winner, Hattie McDaniel. But the enterprising work of Black actors, producers, and directors like Ralph Cooper (who wore all three hats) - also known as the Bronze Bogart and Dark Gable - are largely ignored.Along with white producers Harry and Leo Popkin, Cooper co-founded Million Dollar Pictures, which produced around a dozen films during that four-year stretch, many of them starring the actor. He launched his career with "Dark Manhattan, " a 1937 crime drama that adapted the Hollywood gangster formula with an all-Black cast. Prior to film's opening credits, a title card reads: We dedicate this picture to the memories of R. Harrison, Bert Williams, Florence Mills and all of the pioneer Negro actors who, by their many sacrifices, made this presentation possible.

Cooper also gave Lena Horne her first big break, casting her opposite himself in the 1938 musical, "The Duke Is Tops, " which he also directed and produced. Luckily, both "Dark Manhattan" and "The Duke Is Tops" can both currently be seen. "Manhattan" is part of a double-feature DVD (along with Micheaux's 1937 crime drama "Underworld"), and "Tops" is available on streaming for Amazon Prime subscribers. In both cases, the image quality is subpar at best.

Each would benefit from restoration. On the documentary front, the trailblazing work of William Greaves, beginning primarily in the 1950s, still remains relatively overlooked. Beyond his most well-known films, notably the idiosyncratic, landmark "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One" (1968) - a film that fell into obscurity because distributors didn't know what to do with it, but would be selected for preservation in the National Film Registry 47 years later - Greaves had a pioneering role in documenting and celebrating the Black experience in America.He died in 2014, and the Academy has yet to officially recognize his avant-garde work. It did so indirectly in 2020, when the organization dished out grants to 96 film institutions and programs, including Hamilton College in New York. Hamilton then used the funds to finance a William Greaves retrospective, describing the documentarian as the most accomplished African American filmmaker between the end of the'race film' era in the 1940s and the arrival of'Blaxploitation' and the'LA Rebellion' in the 1970s. It's not hard to get up to speed on Greaves' work. Most of his films are accessible, even if it means making a trip to YouTube; however, several of the pre-WWII titles, including Micheaux films like "The Homesteader" (1919), "The Brute" (1920), and "The Conjure Woman" (1926), are among a long list of Black films presumed to be lost.

These works, no matter how crude (many were made for a pittance, given the lack of financial mobility Black people were afforded at the time), deserve a measure of recognition for existing in the first place. THE STORY OF A THREE-DAY PASS, Nicole Berger, Harry Baird, 1968. "The Story of a Three-Day Pass, " Nicole Berger, Harry Baird, 1968. It's a relief that the industry now recognizes value in the works of Black filmmakers on whose shoulders present-day Black writers and directors stand. Melvin Van Peebles' stylish, Nouvelle Vague-inspired debut, "The Story of a Three Day Pass" (1968) - recently restored and re-released with support from none other than the HFPA, is one example. It was the first feature-length narrative film (on record) directed by an African American since Micheaux's last effort, 1948's The Betrayal. Additionally, Kino Lorber's one-of-a-kind collection, "Pioneers of African American Cinema" (2015), unearthed some lost "race films, " a few by Micheaux, aiming to "shine a long-overdue spotlight on the trailblazing wave of Black American independent cinema" of the early 20th century. The industry is even in the midst of a nebulous "neo-blaxploitation" phase, as studios revitalize interest in what is still considered a contentious period for Black cinema. These once-niche films were made on the cheap, lionized pimps and drug dealers, and oversexualized Black women's bodies; now they're being repackaged and mainstreamed by Hollywood execs, produced with higher budgets and drawing, in some cases, top-shelf talent. "Shaft" and "Super Fly" were remade by major studios; in development are "Cleopatra Jones, " "Foxy Brown, " and Dolemite. In 2017, Martin Scorsese launched an initiative to locate and restore classic African films via his Film Foundation, in partnership with the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO. Dubbed The African Film Heritage Project, 50 films distinguished for their historic, artistic and cultural value were to be identified and preserved. Ultimately, the goal is to protect essential titles to ensure that new generations of African moviegoers can actually see, appreciate, and maybe even be influenced by them rather than the deluge of titles from the West that have flooded African markets for decades. "Race films, " like those by Micheaux, have been neglected in part due to their perceived lack of value and limited reach; it parallels the muzzling of marginalized voices of the period. Note that the 1920s through the 40s had some of the highest concentration of work by Black filmmakers, the likes of which the industry wouldn't see again until decades later. They deserve to be celebrated and their trailblazing work held in the same high regard as their white contemporaries.Hollywood is making progress on celebrating current Black talent; now it's time to take the long view. Oscar Micheaux was the quintessential self-made man. Novelist, film-maker and relentless self-promoter, Micheaux was born on a farm near Murphysboro, Illinois. He worked briefly as a Pullman porter and then in 1904 homesteaded nearly 500 acres of land near the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Micheaux published novels in Nebraska and New York and made movies in Chicago, Illinois and Los Angeles, California. Micheaux left "autobiographical" records in his first three novels, The Conquest (1913), The Forged Note (1915) and The Homesteader (1917), in which his protagonists play out a young black man's life in rural, white South Dakota. Micheaux began his career with door-to-door sales of his early writings to neighboring farmers.Encouraged by the modest success from his first novel, Micheaux gave up farming to write six other novels about this period and region. Griffith's powerful and vitriolically anti-black movie The Birth of a Nation ironically impressed upon Micheaux the ability of a filmmaker to tell a complex, multi-character story every bit as compelling as a novel. Oscar Micheaux soon got the opportunity to test his theory in 1918 when he was contacted by the black-owned Lincoln Film Company in Nebraska to adapt his third novel, The Homesteader, to film. Micheaux rejected the offer and instead moved to Chicago where he made his own film version of his novel. The Homesteader was the first full-length feature film written, produced and directed by an African American.

Oscar Micheaux's desire to control the production and distribution of his films was be the hallmark of his career. He persuaded the best black actors of his time to work in forty-four, mostly low-budget, films he produced between 1919 and 1948 that appealed to the rapidly growing black urban audiences of the post-World War I period. Most of Micheaux's films were detective stories, quickly written, filmed, edited and released.His African American audiences rarely complained since they were starved to see people on the silver screen who looked like they did. Micheaux on occasion tackled more complex subjects in his films. Within Our Gates, his fifth film, specifically attacked the racism portrayed in The Birth of a Nation. He also took on controversial subjects in the black community including interracial romance, skin color hypocrisy and corrupt clergymen. Significantly, his films in the 1920s and 1930s contrasted sharply with the Hollywood image of blacks as lazy, ignorant and sexually aggressive.

Many white critics decried Micheaux's amateur movie-making skills, yet his audiences devoured his product, making him the most successful black writer, producer and director in the United States until his death in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1951. Eventually Hollywood recognized both Micheaux's genius and his crucial role in opening opportunities for African Americans in front of and behind the motion picture camera. In 1987, Oscar Micheaux was memorialized with a Hollywood Walk of Fame Star. Two years later, he was given posthumous awards by the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame (1989) and the Director's Guild of America (1989). Each year Gregory, South Dakota, Micheaux's adopted home town, stages the Oscar Micheaux Film Festival.

The country's first major Black filmmaker, Oscar Micheaux (sometimes written as "Michaux"), directed and produced 44 films over the course of his career. Throughout the first half of the 20th century Micheaux depicted contemporary Black life and complex characters in his films, countering the negative on-screen portrayal of Blacks at the time. Born in 1884, Micheaux tried his hand at a number of vocations before embarking on a film career. Moving to Chicago from a small Illinois town when he was 17 years old, Michaeux shined shoes and worked in the meatpacking and steel industries before landing a job as a porter for the American railway system.

Operating in the first half of the 20th century, Micheaux depicted contemporary Black life and complex characters in his films, countering the negative on-screen portrayal of Blacks at the time. In 1904, Michaeux moved to South Dakota and became a successful homesteader amid a predominantly blue-collar white population. The government's Homestead Act allowed citizens to acquire a free plot of land to farm.Although the act included Black Americans, discrimination kept many Blacks from pursuing a homestead. Michaeux began writing about his experiences on the frontier, submitting articles to the press as well as writing novels. Published in 1913, his first novel The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer was loosely based on his own life as a homesteader and the failure of his marriage. The novel attracted attention from a film production company in Los Angeles, which offered to adapt the book into a film.

Negotiations fell apart when Michaeux wanted to be directly involved in the film's production, and he decided to produce the film himself. After setting up his own film and book publishing company, Michaeux released The Homesteader in 1919. The silent black-and-white film features a Black man who enters a rocky marriage with a Black woman, played by the pioneering African American actress Evelyn Preer, despite being in love with a white woman. REALISTIC PORTRAYALS OF BLACK AMERICANS.Depicting realistic relationships between Black and white people, the film gained praise from critics, one of them calling it a historic breakthrough, a creditable, dignified achievement. Micheaux followed up his successful production with his second film, Within Our Gates (1920), which sought to challenge the heavy-handed racist stereotypes shown in D. Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation.

Micheaux used his films, the first by a Black American to be shown in white movie theaters, to portray racial injustice suffered by Black Americans, delving into topics such as lynching, job discrimination, and mob violence. Given the restrictions of the time, Micheaux's prolific career was nothing short of groundbreaking. The acclaimed filmmaker died in 1951 at the age of 67 while on a business trip. Oscar Micheaux was an African-American homesteader.Like many Black homesteaders, his parents Calvin and Belle Michaux were born enslaved, in Kentucky. They moved across the Ohio River to Illinois, where Oscar was born in 1884. His family grew wheat and corn on their 80-acre farm.

As a young man, Micheaux worked odd jobs in and around Chicago, including as a Pullman porter. As he traveled the nation on a Pullman, he decided to homestead - the prairie called to him. Black homesteaders understood better than anyone the implications of landownership on political and social freedoms and rights. The Emancipation Proclamation, which like the Homestead Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln, declared that all persons held as slaves..

Are, and henceforward shall be free. After Emancipation Blacks sought to build new lives, provide for their families, and educate their children. They especially sought to own their own land, and realize their long denied dreams of working their own farm. They knew how to farm, and saw land ownership as their way to support themselves and their families, and a symbol of their freedom and equality in the United States. Oscar Micheaux traveled to South Dakota in 1904 to participate in a lottery run by the General Land Office to distribute homesteading lands on the Rosebud Reservation.However, with more than 100,000 claimants for only 2,400 homesteads, he was not able to obtain one directly in the lottery drawing. After some success as a homesteader on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, a three year drought destroyed his crops. Oscar was in his field rain or shine, yielding only to frozen ground, plowing up 120 acres in his first year. His determination soon turned his neighbors laughter to a grudging respect, then to acceptance, and finally to admiration, when they realized that he had broken many more acres of prairie than most of them. This admiration left Oscar feeling tentatively welcome in an area where he was the lone African American.

Knowing the delicate nature of race relations, Oscar knew a romantic relationship with a white woman would not be tolerated, even though Oscar had strong feelings for a local white woman and those feelings appear to have been reciprocated. Micheaux married Orlean McCracken, a schoolteacher and daughter of a reverend from Chicago, in 1910 and they had a fraught marriage. When Oscar traveled for work, Orlean felt abandoned. During one of the times he was away, Orlean suffered a miscarriage. Her family did not like having her on the homestead alone, so they traveled to South Dakota and took her back to Chicago with them. Micheaux tried unsuccessfully to get Orlean and his property back. Oscar began writing down his experiences as a homesteader as a way to cope with the hardships he was enduring. His writings were a mix of fiction and biography meant to tell his story of struggle with, and conquest of, the land. He soon had created a full length book that he appropriately titled The Conquest. This new enterprise soon led to a second novel titled The Homesteader.His self published novels were moderately successful, but more importantly they caught the attention of a production company that wanted to turn them into a movie. In 1919, he adapted his story into a film, becoming the first known African-American filmmaker and director. Though The Homesteader (1919) is considered to be a "lost film", it launched Micheaux's career.

Over 30 years he made more than 40 films, and his work has been preserved by the Library of Congress and the National Film Registry as culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant. Micheaux's films featured contemporary African-American life.His works highlighted and worked to combat racism and racial inequality. Black actors in Micheaux's films played the roles of doctors, businessman, detectives, and lawyers. His movies provided a window into black life and the African American perspective on race.

Oscar Micheaux remarried in 1926 to actress Alice B. She appeared in six of his films. Oscar passed away of heart failure on March 25, 1951 at the age of 67, in Charlotte, North Carolina on a business trip. Oscar was buried in Great Bend, Kansas.

His grave stone reads A Man Ahead of his Time. Born: January 2, 1884, Metropolis, Illinois. Died: March 25, 1951, Charlotte, North Carolina. Oscar Micheaux was born January 2, 1884, in Metropolis, Massac County, Illinois, the fifth of 13 children. Many of his family members, including his parents, became early settlers in the area of Great Bend.He left his family's farm at age 17 and worked as a Pullman porter in Chicago. From there he moved to South Dakota and became a farmer and entrepreneur. It was in South Dakota that Micheaux began his career as a novelist.

In 1913 Micheaux published and marketed his first book, The Conquest. At first Micheaux traveled door to door to sell his books to South Dakota farmers and businessmen. He overcame prejudicial attitudes and the restrictions on African Americans at the time and founded his company, Western Book Supply. Micheaux wrote The Case of Mrs.

In 1951 he told the New York Amsterdam News why he wrote and published his own books. I want to see the Negro pictured in books just like he lives. But, if you write that way, the white book publishers won't publish your scripts, so I formed my own book publishing firm and write my own books, and Negroes like them, too, because three of them are best sellers. Micheaux didn't stop at writing books.

He went on to create Micheaux Film Corporation, which became the only black-owned, independent film company to continually operate through the 1920s and 1930s. After rewriting his first book, he produced and directed it in 1919 as the film The Homesteader.This silent film was the first full-length movie produced by an African American. Micheaux went on to produce more than 40 feature length films. He was the first African American to produce a sound film with The Exile (1931).

His last film, Betrayal (1948), was the first African American-produced film to open in white theaters. With limited funds to produce his movies, Micheaux found ways to cut corners. He couldn't afford to re-shoot scenes or film from multiple angles. While his films were sometimes criticized as being technically inferior, he was able to successfully mix entertainment with social messages. Micheaux died in 1951 while on a promotional tour in North Carolina. He claimed two adopted homes, Harlem, New York; and Great Bend, Kansas. Micheaux chose to be buried in Kansas. His tombstone simply read, A Man Ahead of His Time.In 1988 the community erected a monument in memory of this pioneer American filmmaker. Micheaux continues to receive recognition.

He was inducted into the Black Filmmaker's Hall of Fame, which honors him each February by presenting the Oscar Micheaux Award. The Directors Guild of America named him the posthumous recipient of the Golden Jubilee Special Directorial Award in 1986. Also that year he was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Photo courtesy State Archives of the South Dakota State Historical Society.

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux was an American author and film director. Although predated by the short lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company that put out smaller films, he is regarded as the first African-American feature filmmaker, and the most prominent producer of race films. Micheaux was born near Metropolis, Illinois and grew up in Great Bend, Kansas, one of eleven children of former slaves.

As a young boy, he shined shoes and worked as a porter on the railway. As a young man, he very successfully homesteaded a farm in Gregory County, South Dakota, where he began writing stories. Micheaux overcame many of the racist attitudes and restrictions on African-American publishers and authors by forming his own publishing company to sell his books door-to-door.

The advent of the motion picture industry intrigued him as a vehicle to tell his stories. He formed his own movie production company and, in 1919, became the first African-American to make a film. {citation} He wrote, directed and produced the silent motion picture, The Homesteader, starring pioneering African-American actress Evelyn Preer, based on his novel of the same name. In 1924, his film, Body and Soul, introduced the movie-going public to Paul Robeson. Given the times, his accomplishments in publishing and film are extraordinary, including being the first African American to produce a film to be shown in "white" movie theaters. In his motion pictures, he moved away from the "Negro stereotypes" being portrayed in film at the time. In his film Within Our Gates, Micheaux attacked the racism depicted in the D. Griffith film, The Birth of a Nation.Oscar Devereaux Micheaux US: /m? / (About this soundlisten); January 2, 1884 - March 25, 1951 was an African-American author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and controlled by black filmmakers, [1] Micheaux is regarded as the first major African-American feature filmmaker, a prominent producer of race film, and has been described as "the most successful African-American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century".

[2] He produced both silent films and sound films. The Czar of Black Hollywood. Micheaux was born on a farm in Metropolis, Illinois, on January 2, 1884. [3] He was the fifth child born to Calvin S. And Belle Michaux, who had a total of 13 children.

In his later years, Micheaux added an "e" to his last name. His father was born a slave in Kentucky. [3] Because of his surname, his father's family appears to have been enslaved by French-descended settlers. French Huguenot refugees had settled in Virginia in 1700; their descendants took slaves west when they migrated into Kentucky after the American Revolutionary War.

In his later years, Micheaux wrote about the social oppression he experienced as a young boy. His parents moved to the city so that the children could receive a better education. The discontented Micheaux became rebellious and his struggles caused problems within his family.

His father was not happy with him and sent him away to do marketing in the city. Micheaux found pleasure in this job because he was able to speak to many new people and learned social skills that he would later reflect in his films. When Micheaux was 17 years old, he moved to Chicago to live with his older brother, then working as a waiter. Micheaux became dissatisfied with what he viewed as his brother's way of living "the good life". He rented his own place and found work in the stockyards, which he found difficult. [3] He moved from the stockyards to the steel mills, holding down many different jobs. After being "swindled out of two dollars" by an employment agency, Micheaux decided to become his own boss.His first business was a shoeshine stand, which he set up at a wealthy African American barbershop, away from Chicago competition. He became a Pullman porter on the major railroads, [3] at that time considered prestigious employment for African Americans because it was relatively stable, well paid, and secure, and it enabled travel and interaction with new people.

This job was an informal education for Micheaux. He profited financially, and also gained contacts and knowledge about the world through traveling as well as a greater understanding for business.When he left the position, he had seen much of the United States, had a couple of thousand dollars saved in his bank account, and had made a number of connections with wealthy white people who helped his future endeavors. Micheaux moved to Gregory County, South Dakota, [4] where he bought land and worked as a homesteader. [3] This experience inspired his first novels and films. [5] His neighbors on the frontier were predominately blue collar whites. Some recall that [Micheaux] rarely sat at a table with his blue collar white neighbors.

Micheaux's years as a homesteader allowed him to learn more about human relations and farming. While farming, Micheaux wrote articles and submitted them to the press. The Chicago Defender published one of his earliest articles. In South Dakota, Micheaux married Orlean McCracken. Her family proved to be complex and burdensome for Micheaux.

Unhappy with their living arrangements, Orlean felt that Micheaux did not pay enough attention to her. She gave birth while he was away on business, and was reported to have emptied their bank accounts and fled. After his return, Micheaux tried unsuccessfully to get Orlean and his property back. Micheaux decided to concentrate on writing and, eventually, filmmaking, a new industry.

[3] In 1913, 1,000 copies of his first book, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer, were printed. [3] He published the book anonymously, for unknown reasons. He based it on his experiences as a homesteader and the failure of his first marriage and it was largely autobiographical. Although character names have been changed, the protagonist is named Oscar Devereaux. His theme was about African Americans realizing their potential and succeeding in areas where they had not felt they could.

The book outlines the difference between city lifestyles of Negroes and the life he decided to lead as a lone Negro out on the far West as a pioneer. He discusses the culture of doers who want to accomplish and those who see themselves as victims of injustice and hopelessness and who do not want to try to succeed, but instead like to pretend to be successful while living the city lifestyle in poverty. He had become frustrated with getting some members of his race to populate the frontier and make something of themselves, with real work and property investment. He wrote over 100 letters to fellow Negroes in the East beckoning them to come West, but only his older brother eventually took his advice. One of Micheaux's fundamental beliefs was that hard work and enterprise would make any person rise to respect and prominence no matter his or her race. In 1918, his novel The Homesteader, dedicated to Booker T. Washington, attracted the attention of George Johnson, the manager of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company in Los Angeles. After Johnson offered to make The Homesteader into a new feature film, negotiations and paperwork became inharmonious. [3] Micheaux wanted to be directly involved in the adaptation of his book as a movie, but Johnson resisted and never produced the film.Instead, Micheaux founded the Micheaux Film & Book Company of Sioux City in Chicago; its first project was the production of The Homesteader as a feature film. Micheaux had a major career as a film producer and director: He produced over 40 films, which drew audiences throughout the U. [3] Micheaux hired actors and actresses and decided to have the premiere in Chicago. The film and Micheaux received high praise from film critics.

One article credited Micheaux with "a historic breakthrough, a creditable, dignified achievement". [3] Some members of the Chicago clergy criticized the film as libelous. The Homesteader became known as Micheaux's breakout film; it helped him become widely known as a writer and a filmmaker. In addition to writing and directing his own films, Micheaux also adapted the works of different writers for his silent pictures.

Many of his films were open, blunt and thought-provoking regarding certain racial issues of that time. He once commented: It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights. Micheaux's first novel The Conquest was adapted to film and re-titled The Homesteader. [6] This film, which met with critical and commercial success, was released in 1919. It revolves around a man named Jean Baptiste, called the Homesteader, who falls in love with many white women but resists marrying one out of his loyalty to his race. Baptiste sacrifices love to be a key symbol for his fellow African Americans. He looks for love among his own people and marries an African-American woman. Eventually, Baptiste is not allowed to see his wife. She kills her father for keeping them apart and commits suicide. Baptiste is accused of the crime, but is ultimately cleared. An old love helps him through his troubles.After he learns that she is a mulatto and thus part African, they marry. This film deals extensively with race relationships. Micheaux's second silent film was Within Our Gates, produced in 1920.

[6] Although sometimes considered his response to the film The Birth of a Nation, Micheaux said that he created it independently as a response to the widespread social instability following World War I. Within Our Gates revolved around the main character, Sylvia Landry, a mixed-race school teacher. In a flashback, Sylvia is shown growing up as the adopted daughter of a sharecropper.

The landlord is shot by another white man, but Sylvia's adoptive father is accused and lynched with her adoptive mother. Sylvia is almost raped by the landowner's brother but discovers that he is her biological father. Micheaux always depicts African Americans as being serious and reaching for higher education. Before the flashback scene, we see that Sylvia travels to Boston, seeking funding for her school, which serves black children. They are underserved by the segregated society. On her journey, she is hit by the car of a rich white woman. In the film, Micheaux depicts educated and professional people in black society as light-skinned, representing the elite status of some of the mixed-race people who comprised the majority of African Americans free before the Civil War. Poor people are represented as dark-skinned and with more undiluted African ancestry. Mixed-race people also feature as some of the villains.The film is set within the Jim Crow era. It contrasted the experiences for African Americans who stayed in rural areas and others who had migrated to cities and become urbanized.

Micheaux explored the suffering of African Americans in the present day, without explaining how the situation arose in history. Some feared that this film would cause even more unrest within society, and others believed it would open the public's eyes to the unjust treatment of blacks by whites. [6] Protests against the film continued until the day it was released. [6] Because of its controversial status, the film was banned from some theaters. Micheaux adapted two works by Charles W. Chesnutt, which he released under their original titles: The Conjure Woman (1926) and The House Behind the Cedars (1927). The latter, which dealt with issues of mixed race and passing, created so much controversy when reviewed by the Film Board of Virginia that he was forced to make cuts to have it shown. He remade this story as a sound film in 1932, releasing it with the title Veiled Aristocrats. The silent version of the film is believed to have been lost. Micheaux's films were made during a time of great change in the African-American community. [7] His films featured contemporary black life. He dealt with racial relationships between blacks and whites, and the challenges for blacks when trying to achieve success in the larger society. His films were used to oppose and discuss the racial injustice that African Americans received. Topics such as lynching, job discrimination, rape, mob violence, and economic exploitation were depicted in his films. [8] These films also reflect his ideologies and autobiographical experiences. Micheaux sought to create films that would counter white portrayals of African Americans, which tended to emphasize inferior stereotypes. He created complex characters of different classes. His films questioned the value system of both African-American and white communities as well as caused problems with the press and state censors. Critic Barbara Lupack described Micheaux as pursuing moderation with his films and creating a "middle-class cinema". [6] His works were designed to appeal to both middle- and lower-class audiences. Might have been narrow at times, due perhaps to certain limited situations, which I endeavored to portray, but in those limited situations, the truth was the predominate characteristic. It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights. Washington to engraft false virtues upon ourselves, to make ourselves that which we are not.Grave of Oscar Micheaux in Great Bend being decorated during the 2005 Oscar Micheaux festival. Micheaux died on March 25, 1951, in Charlotte, North Carolina, of heart failure.

He is buried in Great Bend Cemetery in Great Bend, Kansas, the home of his youth. His gravestone reads: "A man ahead of his time". Poster for the 2014 documentary film Oscar Micheaux: The Czar of Black Hollywood. The Oscar Micheaux Society at Duke University continues to honor his work and educate about his legacy. 1987, Micheaux was recognized with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

1989 the Directors Guild of America honored Micheaux[9] with a Golden Jubilee Special Award. The Producers Guild of America created an annual award in his name.

In 1989, the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame gave him a posthumous award. Gregory, South Dakota holds an annual Oscar Micheaux Film Festival. In 2001 Oscar Micheaux Golden Anniversary Festival (March 24-25) Great Bend, Kansas. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Oscar Micheaux on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans. On June 22, 2010, the US Postal Service issued a 44-cent, Oscar Micheaux commemorative stamp.

In 2011, the Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia created a category for donors, the Micheaux Society, in honor of Micheaux. Midnight Ramble: Oscar Micheaux and the Story of Race Movies (1994) is a documentary whose title refers to the early 20th-century practice of some segregated cinemas of screening films for African-American audiences only at matinees and midnight. The documentary was produced by Pamela Thomas, directed by Pearl Bowser and Bestor Cram, and written by Clyde Taylor.It was first aired on the PBS show The American Experience in 1994, and released in 2004. In 2019, Micheaux's film Body and Soul was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". The Oscar Micheaux Award for excellence was established. In 2014, Block Starz Music Television released The Czar of Black Hollywood, a documentary film[14] chronicling the early life and career of Oscar Micheaux using Library of Congress archived footage, photos, illustrations and vintage music.

[15] The film was announced by American radio host Tom Joyner on his nationally syndicated program, The Tom Joyner Morning Show, as part of a "Little Known Black History Fact" on Micheaux. [16] In an interview with The Washington Times, filmmaker Bayer Mack said he read the 2007 biography Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only by Patrick McGilligan and was inspired to produce The Czar of Black Hollywood because Micheaux's life mirrored his own. [17][18] Mack told The Huffington Post he was shocked that, in spite of Micheaux's historical significance, there was "virtually nothing out there about [his] life". [19] The film's executive producer, Frances Presley Rice, told the Sun Sentinel that Micheaux was the first indie movie producer. "[20] In 2018, Mack was interviewed by the news site Mic for its "Black Monuments Project, which named Oscar Micheaux as one of its 50 African-Americans deserving of a statue.

He said Micheaux embodied "the best of what we all are as Americans" and that the filmmaker was an inspiration. [21] A historical marker in Roanoke, Virginia commemorates his time living and working in the city as a film producer. The Symbol of the Unconquered (1920). Uncle Jasper's Will (1922). The Virgin of the Seminole (1922).

A Son of Satan (1924). The Conjure Woman (1926), adapted from novel by Charles W. The Devil's Disciple (1926). The Spider's Web (1926). The House Behind the Cedars (1927), adapted from novel by Charles W. The Wages of Sin (1929). A Daughter of the Congo (1930).Ten Minutes to Live (1932). The Girl from Chicago (1932). Ten Minutes to Kill (1933).

God's Step Children (1938). The Notorious Elinor Lee (1940). The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer. Lincoln, Nebraska: Western Book Supply Company.Sioux City, Iowa: Western Book Supply Company. New York: Book Supply Company. The Story of Dorothy Stanfield. This item is in the category "Books & Magazines\Antiquarian & Collectible". The seller is "memorabilia111" and is located in this country: US.

This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Republic of Croatia, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam.

- Topic: Movie

- Subject: Biography & Autobiography